Cómo recordar todo en el aprendizaje de idiomas

Cuando empecé a aprender español mientras vivía en España podrías pensar que yo no necesitaba una memoria a corto plazo; que el mundo que me rodeaba era mi memoria a corto plazo. Palabras básicas que se usan con mucha frecuencia me las repetían todos los días, o muchas veces al día, mientras que las palabras menos usuales seguían llegando a mí pero solo una vez a la semana, al mes o incluso al año, hasta que encontré el camino hasta mi memoria a largo plazo y conseguí aprender. Este es un proceso en el que sigo 15 años más tarde (y también en inglés, mi lengua materna) como un continuo aprendizaje del idioma al cual estoy expuesto a través de escuchar, leer y en general interactuando con el mundo que me rodea.

Sin embargo, aprender un idioma mientras vives en un país donde ese idioma no se habla habitualmente es una historia diferente. Si aprendemos inglés en España, es mucho más duro duplicar la experiencia de aprendizaje y usar la exposición diaria al idioma como una memoria a corto plazo, también como filtro para entender el idioma que realmente necesitas.

Es bastante posible que, como estudiante de inglés, tengas pocas horas de clase a la semana, que complementas a través de deberes, repasando apuntes y buscando cualquier oportunidad para conectar con el idioma en tu tiempo libre (TV, prensa, etc.). La tecnología nos permite tener muchas más posibilidades para hacerlo ahora que hace 10 años, pero obviamente no podemos conseguir el mismo nivel de exposición que podemos conseguir viviendo en un país donde el inglés es dominante. En este caso la carga está en tu memoria a corto plazo para hacer el trabajo que esa exposición no puede hacer.

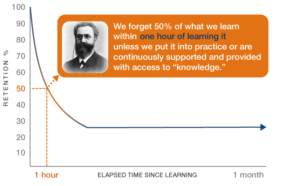

Para ayudar a contextualizar el desafío que esto nos presenta, echa un vistazo al siguiente gráfico el cual muestra la curva del olvido que creó el psicólogo alemán Hermann Ebbinghaus (1885):

Si por ejemplo nosotros descubrimos 10 palabras nuevas en clase, probablemente olvidaremos 5 palabras antes de llegar a casa y otras 3 palabras antes de irnos a la cama. ¡Esto es algo serio!

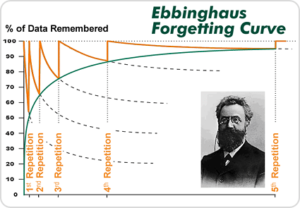

Sin embargo, ¡las buenas noticias es que Ebbinghaus también confirma los resultados de la repetición! Mira el gráfico de abajo:

Por eso en este caso, si nosotros aprendemos 10 palabras y las repetimos 5 veces, es probable que transfiramos 9 de esas palabras a nuestra memoria a largo plazo y las aprendamos. Sin embargo, es vital recordar que para aprender datos o palabras de esta forma, necesitamos usar repetición espaciada. Es decir, no repitas una palabra cinco veces seguidas, o incluso en el mismo día. La palabra necesita ser revisada en intervalos de tiempo espaciados para tener un aprendizaje exitoso.

Por eso, ¿Cuál es la mejor forma para conseguir esta repetición que necesitamos para reemplazar la experiencia de estar rodeado de nuestro idioma objetivo?

Propongo un básico proceso de tres etapas el cual empieza con la introducción de un nuevo idioma en clase o en otros sitios y muévelo a:

Cuadernos

Cuando descubres un nuevo idioma (palabras, frases, etc.), en clase o fuera, necesitas plasmarlo en tus cuadernos. Lo primero que debes pensar es como organizar este idioma en el cuaderno. Varias personas prefieren organizar el nuevo idioma por temas, pero esto puede llegar a ser un problema en niveles más altos donde las palabras son más difíciles de clasificar por categorías. En nuestra opinión, la forma más fácil es llevar el estilo de un diario con el idioma organizado inicialmente por fecha. Como segunda parte, es buena idea filtrar esta información a listas de categorías con áreas de especial interés para ti. Por ejemplo, frases funcionales (Come to think of it…, where was I…?) o palabras con pronunciación difícil.

El segundo factor importante es cómo clasificar el lenguaje nuevo. Aquí están varios elementos posibles para incluir:

- Clase de palabras (Verbos, nombres,..)

- Definiciones

- Una frase de ejemplo con la palabra en el contexto.

- Registro (Formalidad)

- Pronunciación (Quizás usando el IPA – International Phonetic Alphabet)

- Sinónimos y antónimos

- Colocaciones

- Connotaciones

- Frecuencia de uso

- Imágenes/ diagramas

Intenta usar ejemplos, imágenes, etc. los cuales actúan como reglas nemotécnicas, i.e algo que forma una asociación en tu memoria. Por ejemplo:

Lend (v) “Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears” (Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare)

Courage (n)

La gran cosa sobre esto es que tenemos motores de búsqueda para configurar webs de asociaciones para nosotros. ¡Google es una imaginación virtual que puede crear enlaces de memoria para nosotros! Prueba tu palabra entre comillas “…” en un buscador web con “citas”, “títulos de canciones”, “refranes” o busca imágenes. Puedes imprimir y pegar una imagen o dibujarla.

Los cuadernos son una ayuda para la memoria, pero también son un lugar para añadir detalles y dar contexto a las frases o palabras, las palabras no deberían estar aisladas. Una vez que hayas comenzado tu cuaderno debería llegar a ser tu referencia constante y compañero en tu aprendizaje. Si tú no revisas tus notas periódicamente, ¡no te serán de mucha utilidad!

Flashcard Apps

Los cuadernos son una forma esencial para ayudar a reemplazar la necesidad a ser expuesto a un idioma para aprenderlo, ¿pero podemos hacer más? ¿Cómo podemos introducir más “repeticiones espaciadas” para ayudar a mover el idioma a nuestra memoria a largo plazo de una forma correcta e interactiva? La respuesta es con flashcards online.

Nuestra recomendación es la herramienta Anki:

Hay otras opciones de flashcards, tales como Quizlet, pero nos gusta el fácil uso de Anki.

Una vez descargada la herramienta a tu escritorio puedes empezar a crear sets de flashcards, añadiendo el vocabulario y el idioma que necesites practicar. Puedes abrir una cuenta y sincronizarlo a una aplicación en tu móvil u otro dispositivo, ¡pudiendo practicar en cualquier sitio y en cualquier momento!

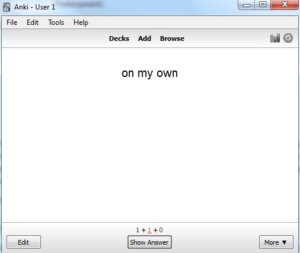

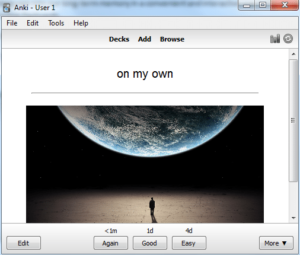

Como puedes ver en las capturas de pantalla más debajo se utiliza como una flashcard física con un frontal y una parte trasera. Puedes usar textos o imágenes para comunicar el significado del idioma objetivo en la forma que prefieras.

De forma complementaria, en la segunda captura de pantalla puedes ver tres botones los cuales dan la oportunidad de indicar si te ha sido fácil recordar la palabra. Regulará con qué frecuencia se repetirá la frase o palabra, creando un sistema inteligente el cual te ayudará a provechar mejor el tiempo.

También tienes la posibilidad de compartir sets de cartas con otras personas.

Es una herramienta de aprendizaje extremadamente poderosa la cual se adapta perfectamente a un estilo de vida ajetreado. Si no la tienes, ¡te animamos a que la uses!

Conclusión

Entonces, lo que hemos identificado es un proceso simple para tener la experiencia de “repetición espaciada” la cual es necesaria para mover un idioma de la memoria de corto plazo a la de largo plazo:

Introducción del idioma de una clase u otra fuente

↓

Cuaderno: contexto y detalles para revisar

↓

Flashcards: información básica para revisar en cualquier sitio y en cualquier momento

Para terminar, con frecuencia hablamos sobre la necesidad del uso activo para adquirir y aprender un idioma, y esto es realmente cierto. Sin embargo, cuando aprendes un idioma en un medio donde otro idioma es el dominante (tal como aprender inglés en España) tenemos que aprovechar oportunidades para compensar la ausencia relativa del idioma que estamos aprendiendo. Coger apuntes buenos es la técnica más vieja, pero es vital en términos tanto de “recordar” como de comprender. Lo que puede ser nuevo para ti es la idea de flashcards electrónicos. La tecnología nos da la posibilidad de seguir estudiando durante pausas que tengamos en nuestro día. De esta forma podemos estudiar durante dos minutos mientras esperamos el autobús o mientras preparamos café ¡y esto marcara la diferencia! Este tipo de tecnología puede ayudar a transformar tu experiencia de aprendizaje en algo motivador y adictivo. El aprendizaje es buscar oportunidades. Nunca antes hemos tenido tantas opciones a nuestro alcance para aprender un idioma ¡así que asegúrate de que las usas y tendrás una clara ventaja!

How can I remember it all? Language learning and memory – a practical proposal for language learners

When I started learning Spanish while living in Spain you could argue that I didn’t need a short-term memory; that the world around me was my short-term memory. Basic ‘high-frequency’ words were repeated at me every day, or many times a day, while less usual low-frequency words were still coming at me but only once a week, or a month, or a year, until they found their way into my long-term memory and became ‘learned’. This is a process that is still going on 15 years later (and also in English, my first language) as I continue to accumulate language which I am exposed to through listening, reading and generally interacting with the world around me.

However, learning a language while living in a country where that language is not commonly spoken is a different story. Learning English in Spain, it’s much harder to duplicate my learning experience and use day-to-day exposure to the language as a short-term memory, as well as a filter to understand the language you really need.

It is quite possible that, as a learner of English, you only have a few hours of class, or less, a week, which you supplement through doing homework, revising notes and looking for any opportunity to connect with the language in your free time (TV, press, etc.). Technology allows us many more possibilities to do this now than 10 years ago, but obviously we cannot achieve the same level of exposure as we can living in a country where English is dominant. In this case the burden is on your short-term memory to do the work that exposure cannot.

To help put into context the challenge this presents us with, take a look at the following graph which demonstrates the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus’s curve of forgetting from 1885:

So, if for example we encounter 10 new words in a class, we will have forgotten 5 probably before we get home and another 3 before we go to bed. A sobering thought!

However, the good news is that Ebbinghaus also confirms that repetition works! Look at the graph below:

So in this case, if we learn 10 words and repeat them 5 times, we are likely to transfer 9 of them to our long-term memory and ‘learn’ them. However, it is vital to remember that to learn data in this way we need to use ‘spaced repetition’. This is to say, it is no use repeating a word five times in a row, or even in the same day. The word needs to be revisited at spaced intervals to allow successful learning.

So, what is the best way to achieve this repetition that we need to replace the experience of being surrounded by our target language?

I propose a simple, three-stage process which begins with the introduction of new language in class or elsewhere and moves on to:

Notebooks

When you encounter new language (words, phrases, etc.), in class or out, you need to record it in your notebooks. The first thing to think about is how to arrange this language in the notebook. Some people prefer to arrange new language by topic area, but this can become a problem at higher levels where words are harder to categorise. In our opinion, the easiest way is in the style of a diary with language initially arranged by date. As a second phase, it is often a good idea to filter this information into additional category lists which represent areas of particular interest to you. For example, functional phrases (‘come to think of it’, ‘where was I..?’) or words with difficult pronunciation.

The second important factor is how to record the new language. Here are some possible elements to include:

- Word class (verb, noun, etc.)

- Definition

- An example sentence with the word in context

- Register (formality)

- Pronunciation (perhaps using the IPA)

- Synonyms and antonyms

- Collocations

- Connotations

- Frequency of use

- Pictures / diagrams

Try to use examples, pictures etc. which act as a mnemonic, i.e. something which forms an association in your memory. For example:

Lend (v.) ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears’ (Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare)

Courage (n.)

The great thing about this is that we now have search engines to set up webs of associations for us. Google is a virtual imagination which can create memory links for us! Try your word in quotation marks “…” in a web search with ‘quotes’, song titles’, ‘sayings’ or look at images. You can print and paste an image or copy it as a sketch.

Notebooks are an aide memoire, but they are also a place to add detail and context, so that the individual language items do not exist in isolation. Once you have begun your notebook then it must become your constant reference and companion in your learning. If you do not periodically revise your notes, then they are not of much use at all!

Flashcard Apps

Notebooks are an essential way to help replace the need to be exposed to language in order to learn it, but can we do more? How can we introduce more ‘spaced repetition’ to help move language into our long-term memory in a convenient and interactive way? The answer is with online flashcards.

Our recommendation is the tool Anki:

There are other flashcard options, such as Quizlet, but we like the easy-to-use functionality of Anki.

Once you download the tool to your desktop you can start creating ‘decks’ of flashcards, adding in the vocabulary and language that you need to practice. Then you can open an account and synchronise to a mobile app on your phone or other device, so you can practice anywhere and at any time!

As you can see in the screenshots below it works like a physical flashcard with a front and a back. You can use text or images to communicate the meaning of the target language in the way you prefer.

Additionally, in the second screenshot you can see three buttons which give the chance to indicate how easily you remember the language. This will then regulate how frequently that item will be repeated, creating an intelligent system which will help make the most of your time.

You also have the possibility to share decks of cards with other people.

This is an extremely powerful learning tool which adapts perfectly to busy lifestyles. If you haven’t already, we urge you to give it a try!

Conclusion

So, what have we have identified is a simple process to provide the experience of ‘spaced repetition’ which is necessary to pass language from short-term memory to long-term memory:

Introduction of language from class or other source

↓

Notebook: context and detail to revise

↓

Flashcards: basic info to revise anywhere and anytime

To finish, we often talk about the necessity of active use to acquire and learn language, and this is certainly true. However, when learning language in an environment where another language is dominant (such as learning English in Spain) we have to take advantage of opportunities to compensate for the relative absence of the language we are learning in our daily lives. Taking good notes is the oldest technique in the book, but it is vital in terms of ‘remembering’ as well as understanding. What may be new to you is the idea of electronic flashcards. Technology affords us the possibility of fitting study into the gaps and pauses of our lives. In this way we can study for two minutes when we are waiting for the bus or for the machine to produce our coffee and it will make a difference! This kind of technology can help to transform your learning experience in a motivating, even addictive way. Learning is about looking for opportunities. For language learning we have never had so many options, so make sure you are using them to give yourself a clear advantage!